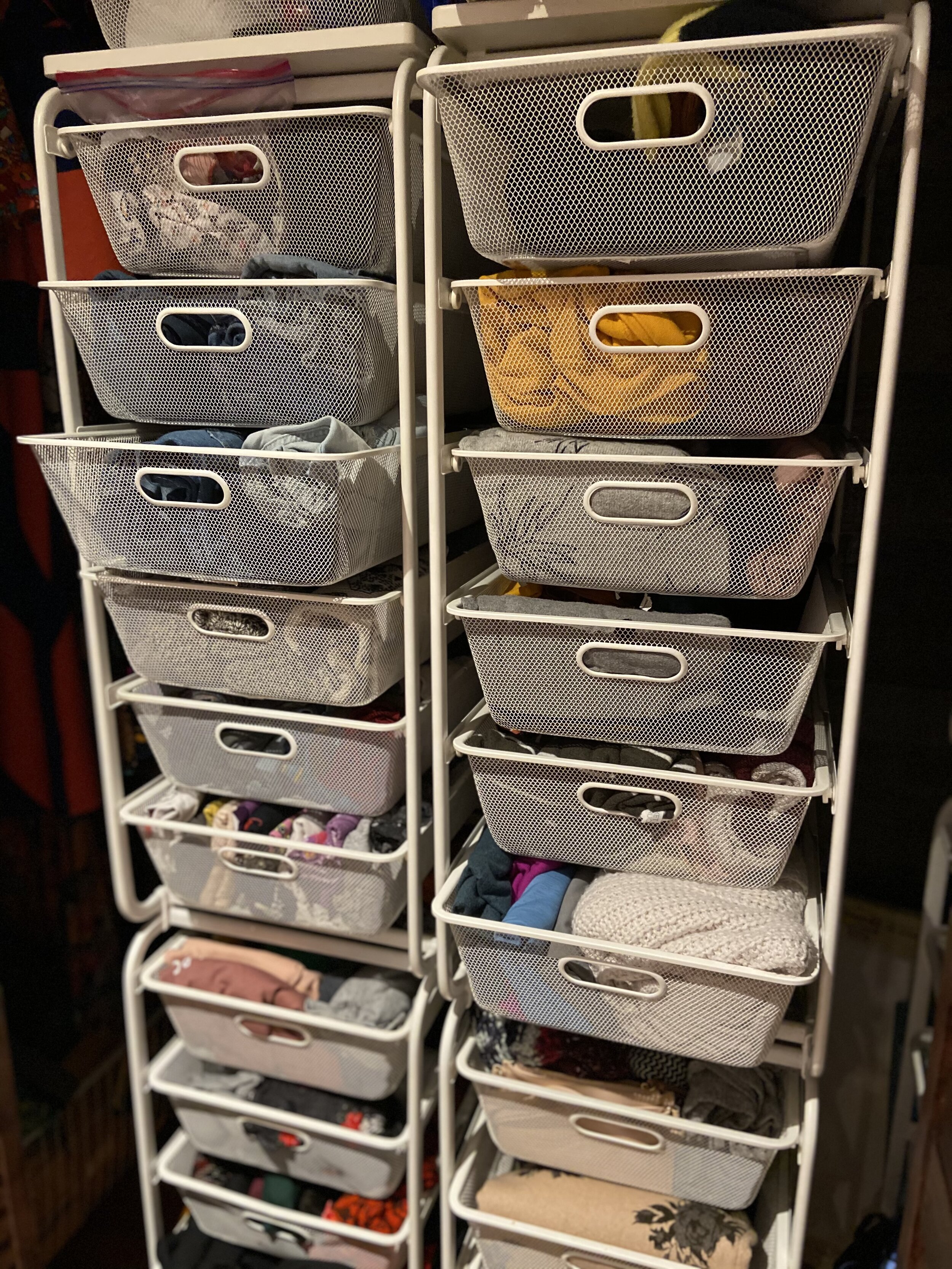

I have too many clothes. I mean, there are multiple closets, shelves, hangers, and drawers. A strange thing to complain about, I know, but between reading all about Death Cleaning and watching Marie Kondo’s multiple shows, I can’t help but wonder why I need all this shit when I wear no more than roughly ten percent of it. Literally, why have hanger upon hanger of dresses, mesh drawer upon mesh drawer full of pants other than the fact that I can now afford to give them all a home? Surely, that’s not a good enough reason, and yet here I am, elbow deep in an attempt to spring clean a week too late-my kid’s school having already completed its clothing drive fundraiser.

The clothes!

So many clothes!

Growing up, age six through eleven, I wore a school uniform a decidedly deep shade of brown five days a week. Much like most clothes we wore, the uniform wasn’t washed in between wears, earning its turn to be laundered roughly once a month (though a fresh collar was attached to it weekly-we weren’t savages!). On Saturdays in 5th grade, however, we got to wear whatever we wanted. Whatever we wanted was, of course, inevitably limited to whatever we had, which wasn’t much. In my case, it was whatever happened to be inside the shiny Czech closet in our living room. More specifically, it was whichever items of my sister’s wardrobe I could fill out at my ten/eleven years of age, my sister being catastrophically thin and me never being thin enough. To me, her clothes were the epitome of what the future could hold. Having lived with us through college and first job, on her days off, she would frequent the outdoor market where pensioners sold loot from the recently permitted trips to Poland, where they would peddle their own crap and purchase Western clothes (mostly sweaters or denim skirts ornamented with white strips of lace) to peddle back to us. There, she’d treat herself to a blouse or a pair of pants roughly on a weekly basis. Once “free form” was permitted in 1993, I could wear one of the two pairs of my sister’s jeans-one high waisted and acid washed (the same pair I would later travel to America wearing) and a skinny, stretchy black pair (the same one I would later stick a wad of gum into during lunch at my Brooklyn junior high where a lunch aid would scream, “no gum chewing” with alarming regularity and, thus seal the pocket forever). On Sundays, too, when I’d go to a few hours of quasi-Hebrew school at a local dilapidated synagogue I was allowed to wear my sister’s clothes. I was probably one of the coolest kids dressed on any given weekend…but then the weekend would be over and back into the itchy, poop-brown dress I’d go.

The decidedly brown school uniform with a dress white apron (the daily one was black)

I did have my own clothes. There weren’t many (on account of constant growth and having a mandatory school uniform), but my favorites were my American second hand items. My dad, like many in the immediate aftermath of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, had an entrepreneurship gig on the side of his nine to five job. Namely, he had a small, hole in the wall shop that sold liquors, lycra pentyhouse (heresy, I tell you!!), and chocolate-all European! Unironically, the shop’s name was as tacky as it was unoriginal (Marseilles!), no one involved in the venture having ever been anywhere past the confines of the USSR, let alone France. The name certainly wasn’t the idea of the city’s Association of People with Disabilities, from whom dad’s little venture was leasing the space. It is through a host of charities that this organization received a rather impressive shipment of American donations one year. A clothing drive, probably not unlike the one I just under-delivered to at my kid’s school, must’ve been held somewhere in the United States, and these Bobruisk folks with various disabilities were the intended beneficiaries. Only the country was starving so only the president and the immediate assistants benefited free of charge; the rest of the folk had to pay. And, though none of us qualified on basis of any disability, because my dad’s business was an important source of income for the Association, our families too got to partake-first dibs among the paying clientele, no less. Winning! Those were some good dibs, too! Ah, that mustard colored plush skirt with a zipper down the front and a pair of Timberland boots made me feel so American. Our impending immigration on my mind, I imagined that all my clothes would look like that once we moved. Actually, the dream was that on the other side of the ocean, I’d eventually have enough clothes to change outfits everyday, just like I watched them do in the Latin American telenovelas they’d started showing us on TV daily. Apparently, rumor had it, it was a hygiene consideration, let alone a statement of your socio-economic status, this whole changing clothes everyday thing. To have an outfit for every day of the week-ah to dream! On TV, the outfits also never repeated (ever!). I figured that was probably a bunch of baloney but I liked it, in principle.

When I finally did come to America, I had very little of my already tiny wardrobe traveling west with me. I had very few prized possessions but my sister informed me that my favorite pink shiny leggings and green bicycle shorts were a no-go because, allegedly, only hookers wore those in America. So, instead, I’d brought the same items I’d by then officially inherited from my sister. In addition, some other things made it into our misshapen suitcases, like all the random summer ensembles bought at the same outdoor market where my sister liked to shop. Besides these things, I had nothing. My grandma (who’d made the move three years ahead of us) claimed that she had everything prepared for me, therefore there was no need to bring clothes for me. We were to save the luggage space for pots and pans and sewing kits. Unfortunately, a few days into my American tenure, I discovered that what grandma meant was that she had a couple of black garbage bags of clothes collected from various neighbors’ daughters waiting for me in her studio apartment hallway closet. None of them fit or were remotely age-appropriate. So much for my American wardrobe getting off to a good start. Back to the drawing board whilst wearing my faux leather sandals with socks.

My cousins removed once, twice or thrice rushed to the rescue (the western way of enumerating relations still confusing to me despite that one Trusts & Estates class in law school). They were older and taller but it worked. More than that-it saved me. It did bother me that these weren’t my items, and that they had a vague smell of someone else’s detergent no matter how many times we washed it in our building’s basement laundry room using our own 99c one, but I had enough clothes to change an outfit every day of the week once school started, as the reported cultural expectation dictated. In fact, I had exactly five changes-just enough for a school week (if I ever showed up all five days in one week that first year in America, that is). I was otherwise miserable, of course, swallowed whole on the daily basis by an overcrowded school buzzing in a language I did not understand but, at least, I was dressed fairly well while crying in this classroom or that.

The black jeans I inherited from my sister (this is after their pocket has been sealed shut with gum).

One of my most prized possessions—this Polish sweater I’d inherited from my sister.

Still, family donations weren't enough for the first fancy party my family was invited to in the spring of our first year here. The whole entire restaurant was being closed down for this shindig and none of my clothes were appropriate-neither my jeans with the no longer functional pocket nor my $10 plaid skirt. Shopping for this ball wasn’t in the cards simply because our budget didn’t allow for a one-event fancy dress for me. Fortunately, given that I’d stopped routinely weeping at school sometime around March and this was May, by then I’d gotten a few people in my circle who were okay with my calling them friends. One of these girls had a lean, slender body and a cousin with what seemed like way more money to all of us back then than it would now. This cousin had bought Jane a dress for some bar-mitzvah and generously, with her parents’ permission, she allowed me to borrow it for the party. It was velvet and featured a bead and/or pearl pattern. It had poofy sleeves and some sort of a ruffly bottom and it was glorious. Zipping me into it was no small feat, and I was a little too proud for not busting its zipper (because no way would my family be able to afford fixing it), but I will be forever grateful to a blonde girl named Jane whom I likely would not recognize walking down the street today. One day, I swore back then, I wouldn’t need hand-me-downs and friends’ rentals.

My rented gown. We’d bought the shoes at the $10 store.

It is no surprise, then, that when I got my first job paying above minimum wage, I shopped (stil cheaply, of course) and shopped some more. Affordable clothing and even a tiny bit of fairly disposable income (I was living with my parents and my sole expense was a metro card and lunch by then) meant I could afford some decent variety. It turns out that’s what I’d been after all along-to have more than five outfits, to repeat less often, to be like the ladies of the New World television. In high school, I had three pairs of jeans (all Levi’s!) and probably ten tops (thanks, Saks 5th Ave OFF 5th). In college, it was five pairs of jeans and roughly fifteen tops. By law school, it was seven and twenty. Now, it’s fifteen and figurative infinity. It’s all the little Soviet child inside me ever wanted but the kicker is that I still wear no more than ten percent of it all so what’s the functional difference? I only like looking at it all, folded and hung neatly, as if the sum of all the contents of these multiple shelves and hangers are a positive summary of my life thus far. It’s all sorts of telling and horribly depressing. Now I feel cluttered and simultaneously ungrateful for my riches. It doesn’t take a graduate degree in psychology to understand the metaphorical dependency here-I shop because I can, because I want to make up for all the years I couldn’t. Still, it’s starting to feel gluttonous. Surely, it’s the opposite of the intended and expected effect of all this accumulation. No one needs forty t-shirts and fifteen pairs of shorts living in the Northeast. No one needs five pairs of dress pants and twelve blouses when she doesn’t have an office job or go out. Maybe someone else can benefit from my greed. Maybe some girl out there will find the joy in my second-hand clothes and the cycle will begin again.

Now, what to do with the hangers?!